14 minute read. Content warnings: References to fatigue, and depression.

chatGPT Summary: Kay begins the ninth year of their annual self-directed October residency. They return to basics in light and shadow after last year’s first foray into shadow puppetry. Day one explores three sources—flashlight, flame, and projector—through sketches and notes, building a vocabulary for what light can do.

This is my ninth year in a self-directed residency. Every October since 2017, I’ve taken this month to step away from paid work and focus on my professional practice. What started as a way to test out prompts and challenges has become a rhythm in my creative life—a space for risk, for trying, and for remembering that play and experimentation are part of growth.

This year, I am focused on light and shadow. I began to explore this last year during my FLEET residency on Granville Island, when I jumped straight into shadow puppetry with little preparation. I realized, quickly, that I was trying to run before I had learned how to walk. I didn’t have enough technical skill or practice to hold the ideas I wanted to develop. So for this residency, I am returning to basics.

The original purpose of this annual practice was to explore techniques and materials I collect during the year. As a preparator and exhibition designer, I accumulate scraps, tools, and challenges from other artists’ projects—things I am curious about but don’t have time to try while working. Lighting has been one of those areas. I’ve spent more than a decade lighting exhibitions, but that knowledge is situational: learning the quirks of each gallery’s system, finding compromises, working within limits. I know far less about staging, puppetry, and formal lighting practice. Part of this month will be reading and research to start filling those gaps.

Over the years, I’ve also learned something about myself: I find the most success when I simply commit to trying. The years that disappointed me most were the ones where I set concrete goals—make a series, finish a project—and then fell short. My instinct is to punish myself when I don’t succeed or exceed my own expectations. I forget that my practice is built on mistakes, failures, and ongoing development. The most important lesson I can carry into this ninth year is to play without demanding a product, and to let the process be the outcome.

This year also feels different physically. In past years, depression sometimes kept me from working, but October was still a time of renewal—a moment when the energy returned. Now, for the first time, I find myself wrestling with a kind of exhaustion that isn’t depression. It is bone-deep tiredness, a body that insists on slowing down. I’ve never felt fatigue in this way before. If I were to set a single goal for this residency, it would be this: to respect the need for rest. To take breaks. To go slower. To practise what I tell others—that rest is important, and it too is a form of work.

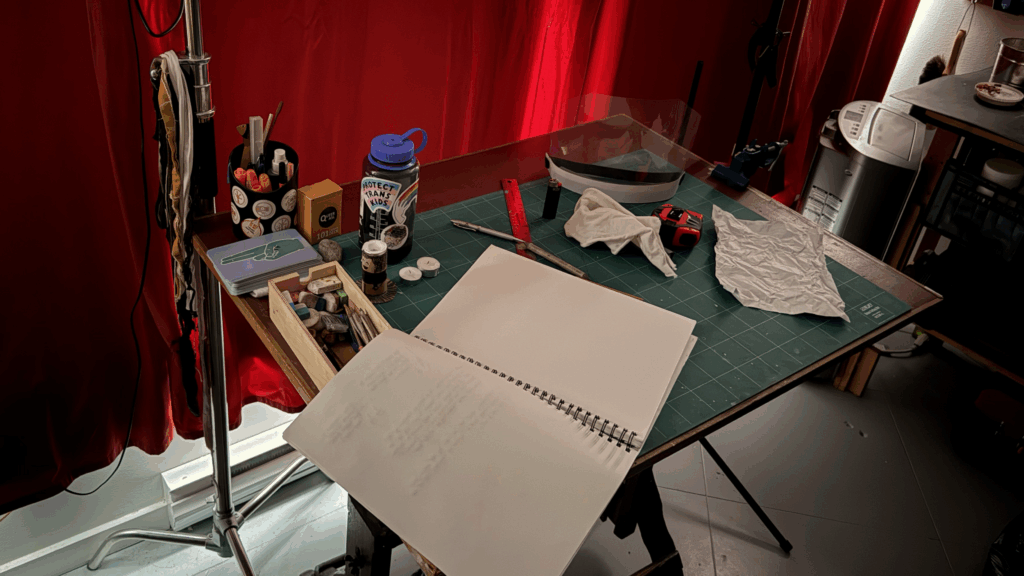

With all of this in mind, I set myself a simple, clear goal for the first day: explore my materials. Nothing grand. Nothing performative. Just as in illustration practice, where a sketchbook might be filled with pages of shading, hatching, and mark-making for future reference, I imagined: what if I could draw with light? What if I could build a sketchbook of shadows? So I pulled out my notebook, set up my lights, and began to make notes.

Flashlight

The first source I reached for was a familiar one: a small LED flashlight. I sat with my large sketchbook open—an 11×17 spread, the kind of space that allows me to make bold gestures or precise tracings—and I began by simply shining the beam down onto the page.

I immediately found myself writing about things that feel basic: the diameter of the light’s face, the size of the hotspot, the subtle yellow cast. But of course, this is where vocabulary and attention begin. I realized very quickly how limited my language is when it comes to describing light, and one of my early intentions for the month crystallized: I want to build a deeper vocabulary, not just of how light behaves, but of how I can articulate what I see, so that I can describe, repeat, and eventually compose with it.

At one centimetre from the page, the flashlight created a small core of brightness about the same size as the bulb’s face. Surrounding this was a dim corona, about two centimetres across, before the light fell off into shadow. Even raising it to five centimetres changed everything. The hotspot expanded, the illumination became more diffuse, and I noticed how quickly the gradient from light to dark shifted outward. At fifteen centimetres, the defined circle disappeared altogether—the light was no longer a shape, but an atmosphere.

I drew each of these changes, tracing the boundaries where brightness gave way to dimness, noting distances, marking gradations. Building a library of shadow.

Tilting the flashlight created a semicircle of illumination, and here my hand began to intrude. Cupped near the beam, it reflected pink light back onto the page. I was reminded of childhood games of shining a torch through our palms, marvelling at the blood and veins lit from within. This time, I realized how much of that colour wasn’t just translucency, but reflection and bounce. My hand became not just an obstacle but a second light source, scattering rosy tones into the shadow.

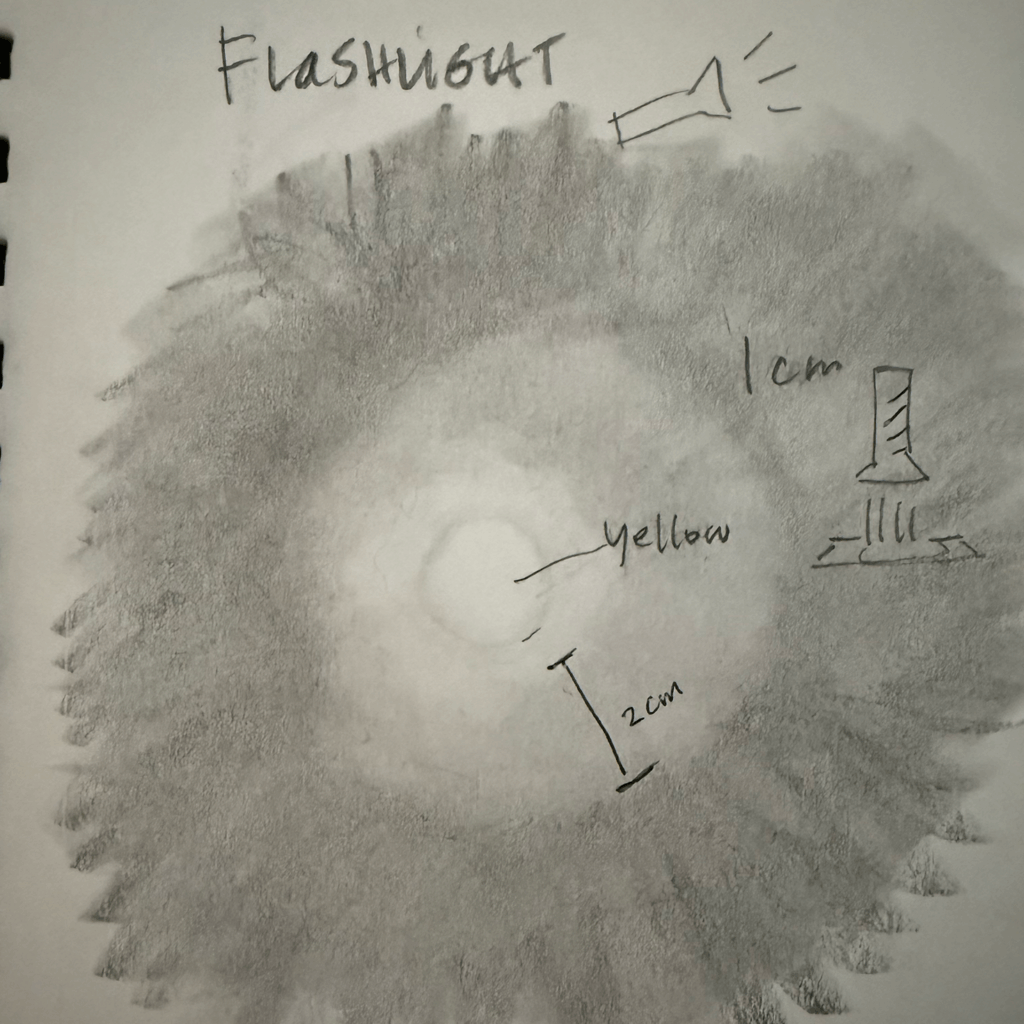

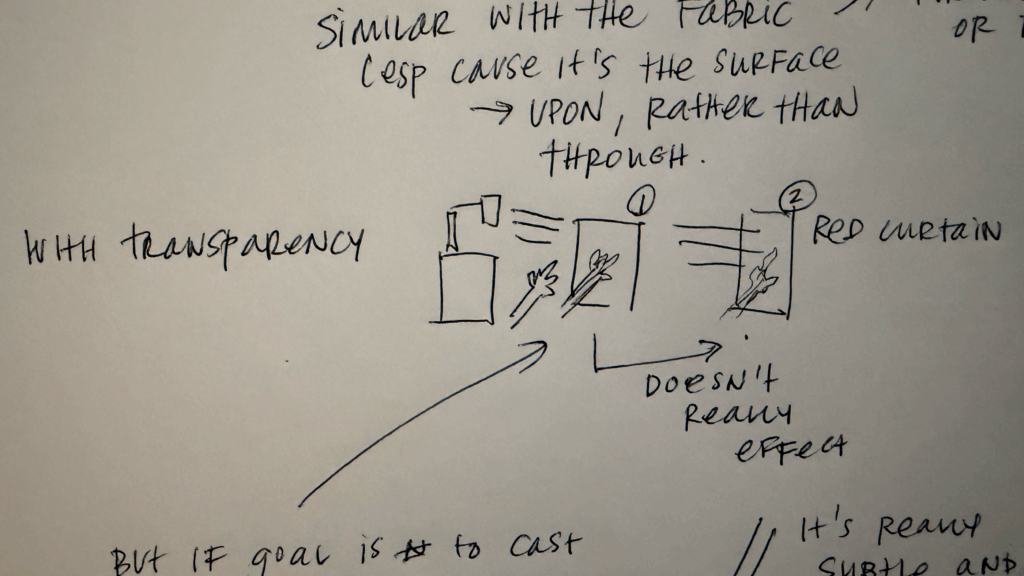

Surfaces mattered too. On copy paper, the diffusion was smooth and the shadows crisp. Wrinkling the sheet gave a moody gradient—texture adding interest rather than distraction. Cotton, by contrast, was uncooperative. The flashlight pierced straight through, creating an unforgiving hotspot. My transparency, on the other hand, surprised me. A clear plastic sheet, left over from a pandemic sneeze shield, produced ghostly, doubled shadows reflected on its surface. My mind raced with possibilities: layering sheets, catching double projections, creating illusions of depth.

Already, I was confronted by one of my favourite residency’s milestones: the moment when curiosity overwhelms assumptions. I had expected the paper to behave but I had dismissed the plastic before even trying it. Silly past me.

Flame

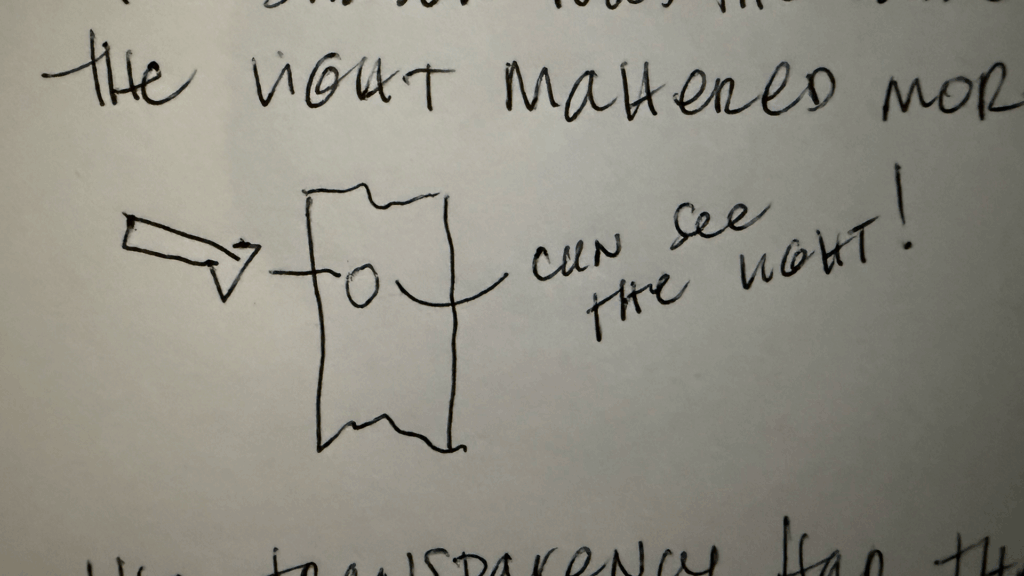

From the flashlight I turned to a more ancient light: a candle.

Immediately my body reacted differently. With the electric torch, I could move casually, carelessly, without consequence. With flame, my heart rate rose. My breath became something to control. I later laughed with my partner that I was grateful for modern light, where the danger is hidden in grids and wires. A candle on paper in a small studio is a visceral reminder of fragility.

The candle’s light was truly yellow—not the cool tint I’d mistaken in the flashlight. Shadows shifted in hue, and the paper revealed textures I hadn’t noticed before: subtle depressions, fibre patterns, small scallops of shadow-like scales.

I placed the tea light into the hollow of a toilet roll tube, creating a seven-centimetre candle holder, and traced the zones of brightness and darkness around it. The shadow seemed greenish, maybe coloured by my cutting mat below, but maybe also a trick of perception? Something else to explore – what colour is shadow? Cupping my hands above the flame, I created once again a wash of pink glow, a reflected diffusion that changed the quality of shadow.

But flame came with limits. To get crisp shadows, I had to bring the candle close to the paper, hovering at anxious distances of five to ten centimetres. Too close! My minor hand tremors made me aware of how easily an accident could happen. And while the flickering light had an undeniable charm, it also lacked the consistency needed for controlled experiments. The romance of flame was real, but so was the risk.

I am not dismissing it; fire is appealing. The energy of staring into a flame, the softness of a flicker—it is very classic to find oneself dreamily losing time before a flame. But I am undecided on how much energy I want to put in this direction.

Projector

Finally, I pulled out my overhead projector.

This light was overwhelming. It filled my space. Wrinkles and imperfections on paper disappeared under its intensity, and yet, the more I stared at the surface, it took on the look of skin, its fibres illuminated like veins or cells.

Objects placed directly on the glass cast shadows with sharpness and odd chromatic halos: blue on one edge, yellow on the other, a distortion I had never noticed before.

Unlike the candle, which charmed and unnerved me equally, or the flashlight, which provided nuance and control, the projector was loud and unrelenting. It erased as much as it illuminated, forcing me to confront how overpowering brightness can flatten detail.

Reflection

Across all three experiments, I kept circling the same questions:

- how do I describe this?

- how do I record it in a way that will serve me later?

My sketches tracked hotspots and gradients. My notes tried to pin down colour shifts and textures. But photographs feel inadequate—light is always different in person, shadows lose their nuance when flattened into pixels. I am also not the best photographer – I like making more than documenting.

So I focused on being present and gaining awareness. Of vocabulary gaps. Of safety concerns. Of how surfaces and distances completely alter what we see.

I ended the day with as many questions as answers:

- Is fabric always going to betray the hotspot? Are my tablecloths just too cheap and low-thread count? Perhaps my mom’s fabric supply will yield different results?

- Are reflected shadows on transparency usable in performance, or are they only interesting in studio play?

- Do I prefer working on the same side as the viewer, casting onto a surface, or behind a screen, hidden from sight?

- And most of all, how can I develop a language—visual, verbal, tactile—for what light does?

Tomorrow, I will return to the sketchbook and keep building this small vocabulary. After some gentle play with light sources, I am going to focus on distance, scale and blur tomorrow.

Day one reminds me that discovery doesn’t need to be spectacular. It can be the act of noticing the colour wash of reflected skin, or the way paper suddenly looks like flesh. Not a bad start. Now it’s time for a rest.

Technology note:

I continue to test the use of AI within my writing and artistic practice. I used otter.ai to transcribe my thoughts and chatGPT to create a summary and reading estimate and recommend some content warnings for this blog, and Antidote 12 to assist me in spelling and grammar.